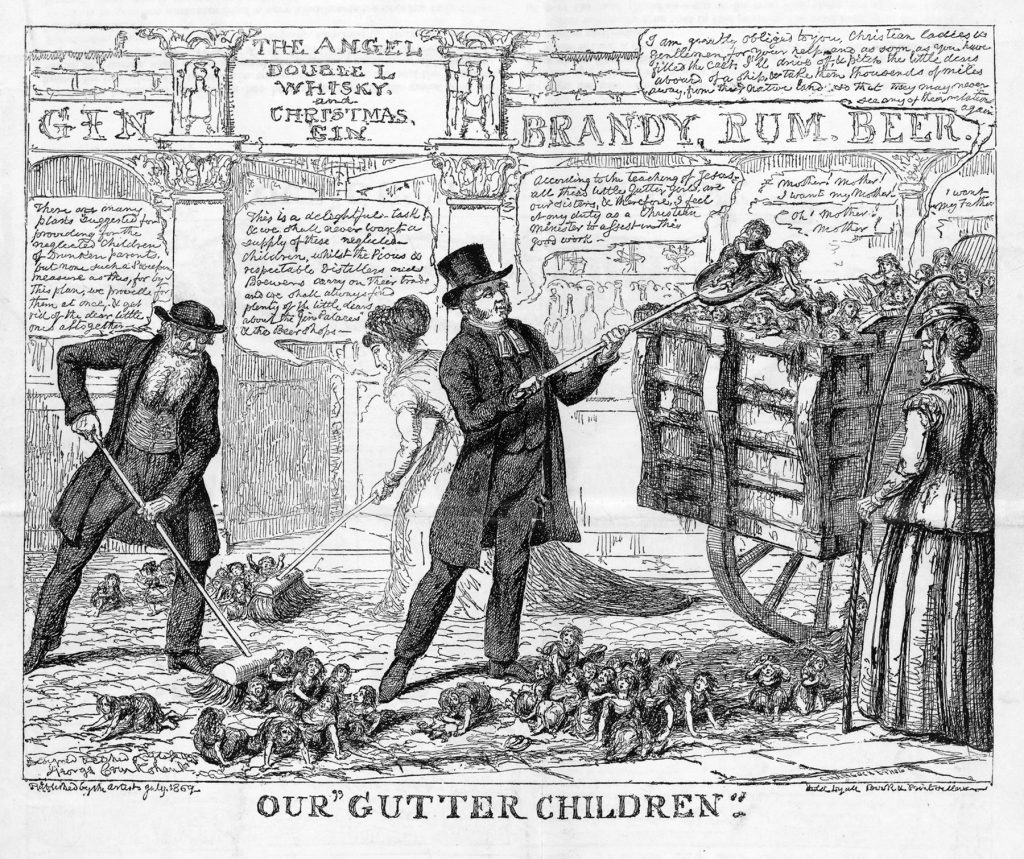

Behind the Scenes

(Learn more about the graphic here)

Notes on the British Child Migration

DR. BARNARDO AND THE BRITISH CHILD MIGRATION

The British Child Migration, a social program conceived to deal with over population during the nineteenth century, rid Britain of thousands of poor children by sending them off to the colonies. Barnardo’s was the largest of several different organizations involved.

In 1866, Thomas John Barnardo, the ebullient son of a Dublin merchant, went to England to study medicine. His intention of becoming a medical missionary in China was derailed by his efforts to help the poor street children of East London. He started Ragged Schools and took desperate boys into his first children’s home on Stepney Causeway. Realizing that the poverty epidemic affected all British cities, he opened Ever Open Door Homes, satellite centres across the country, where children could be dropped off day or night without explanation. They were quickly moved to larger facilities, generally in or near London. Within a few years, what began as a well-intentioned but haphazard program for these children grew into a network of homes that accommodated close to nine thousand impoverished boys and girls. This rapid expansion was made possible through the generous donations from his many affluent and middle-class supporters. Dr. Barnardo was equally at home preaching Evangelism and abstinence on the streets of East London or canvassing for money in the stately drawing rooms of titled philanthropists. His natural enthusiasm and charm opened doors and pocketbooks.

***

Complex socio-economic conditions led Britain to heartlessly deport its most vulnerable citizens to Canada. Some youngsters thrived in good homes with loving families, while others were callously exploited as unpaid child labourers. They had no rights, no agency to protect them, and no Canadian citizenship. All had been stripped of their British identity and permanently separated from their biological families, while obstacles were deliberately placed in the way of reunification.

Between 1801 and 1901, the population of England and Wales increased from less than ten million to more than thirty-two million. In the 1841 census, the first to analyze demographics, forty-five percent of the population was reported to be under the age of twenty. The momentum for this growth started around 1750, when numbers began to recover following the last plague, one hundred years previous. Alcoholism was rampant. Everyone drank pale ale because the water wasn’t clean, and it was a small step from ale to gin. By 1850, due in part to mechanization and the collapse of the feudal system which forced families off the farms, English cities were overrun with desperately poor people. Despite the harsh living conditions, young people married earlier than ever before and fertility rates increased. Multiple children earned an income for the family and provided insurance against high rates of infant mortality. By the 1880’s, with the introduction of laws to protect child labourers and to provide mandatory schooling, children had become expendable. The British Child Migration program circumvented British labour restrictions by exporting them to Canada, where such limitations in rural areas were difficult to enforce, since farm needs often took precedence over schooling.

***

Approximately ten percent of Canadians are descended from British child immigrants, but most aren’t even aware of the dirty little secret in their heritage. Their ancestors were too traumatized or humiliated to tell anyone about it, because they were accused by the press at the time of being physically or mentally defective, immoral, troublesome, diseased, lazy and likely to commit heinous crimes upon the innocent farmers who took them in.

“These gutter children will break the law and contaminate our pure Canadian gene pool,” the muckrakers railed. “Britain is sending us its unwanted trash!”

When they first entered the system back in England, the children were shabby, semi-literate and lice-infested, but not necessarily unwanted. Tragically, most were not orphans at all. They were lied to-convinced that they had no family when in fact they did. Some came from the streets, some were seized from unfit parents, but thousands were taken from workhouse families or came from poor but loving homes where the parents had inconsistent employment, fell sick or died. In desperation, these families surrendered their young to Evangelical guardians who promised to provide them with care and education. Some lucky children received these things, but many others were cleaned up and quickly shipped off to the colonies to become indentured farm labourers or domestics. They were assured of an exciting life in the land of milk and honey-a country brimming with resources and starved of citizens-but their experiences were often very different from their expectations.

While the system functioned successfully in Britain, providing a safety net for parents and a healthy, productive lifestyle for the children, it often fell apart in Canada when children were scattered like seeds tossed into the wind. Many very young boys worked gruelling hours with little more than a meal and a bed at the end of the day. Some slept in barns, went without shoes and coats, suffered beatings and sexual abuse, were denied education and adequate nutrition. Others, who were spared such indignities were treated as the help, not as family members. In fact, often farmers cared more about the hired men than they did for the home boys.

Girls were the most vulnerable to sexual assault. Pregnancies were so common that Barnardo’s opened a receiving home in Toronto to accommodate the girls during their confinement. Seven young women, aged fifteen to twenty-two, were living in the Home for Fallen Girls at 214 Farley Avenue, when the 1901 census was completed. The Child Welfare Council of Canada investigated the records at Toronto General Hospital to determine who was responsible for 124 pregnant teenagers who had given birth there and claimed to come from Barnardo’s. Editors wrote, “Barnardo Homes have contributed toward the problems of illegitimacy and feeble-mindedness in Toronto, considerably more than their quota.”

When Maria Rye, a woman who acquired children from the Church of England’s Waifs and Strays Society, was asked about a pregnant twelve year old in her care, her answer reeked of hypocrisy.

“That’s what you get when you take in street arabs,” she claimed.

For years, rumours circulated concerning the inappropriate behaviour of Barnardo’s Canadian Superintendent, Alfred Owen. Countless complaints by his associates were ignored back in London. In 1919, he was charged with cohabiting with, and impregnating a home girl, Mafey Skelton, who was thirty-nine years younger than he. She posed as his housekeeper, while his wife and children lived in Muskoka. Mr. Owen was arrested and released on a $2000 bond. He provided a written statement admitting his guilt, but the case never went to trial, and he left his post. The very man who’d been trusted with the responsibility of protecting these children betrayed them. In December 1924, Mafey travelled to England-under the name of Mafey Owen-where she gave birth to a baby girl. She returned to Canada in October 1925, without the child, and reunited with Alfred Owen in Kelowna B.C.

***

Integration of home children didn’t go smoothly. Virtually all of them were city born and unprepared for rural life, isolation and harsh Canadian winters. They arrived with insufficient clothing and no experience in farming. Sadly we’ll never know the extent of the neglect and abuse: some ran away, some died, some committed suicide and at least two were murdered.

One boy died from a beating. The woman who perpetrated this heinous crime was tried and acquitted, despite the damning evidence given by her neighbours, and the coroner’s statement that he had never seen such a horrifying murder scene. Her defence:”The boy was a lazy lout.”

A second boy had his throat cut and his body burned in a fire. The coroner determined his death to be a suicide. Other such questionable deaths were covered up or never investigated.

***

How could Britain justify dumping its most important resource on to Canada’s welcome mat? How could the Canadian Government explain that it paid head fees for these human beings? It was surely a difficult and complicated situation, with no simple solutions to the problems facing Britain and Canada. Complex socioeconomic conditions created the need for the child migration. Empathy was the ignition but, in the end, it played a small part. Both countries cooperated in what amounts to legalized child trafficking-a crime punishable nowadays by a lengthy term in a federal prison. Four years after the U.S. abolished slavery in 1865, Canada started accepting British children labourers under the guise of adoption. In defusing a tenuous political situation in Britain, and at the same time providing the necessary workers for Canadian farms, the British Child Migration seemed to be a win/win situation-good for Canada, good for Britain. No one considered the needs of the children, who were seen as just a commodity.

It’s puzzling that an issue of this magnitude has slipped under the radar. Between 1869 and 1948, more than 100,000 children came to Canada, unwillingly, and yet after one generation they blended in without so much as a whimper. Over the eighty years that the program operated, the logistics were staggering, the expense enormous, and the human cost inestimable. Thousands of dollars must have changed hands with little accounting required-money from both governments, from application fees and from private benefactors. Even the working Barnardo children had to donate to a fund. The entire scheme remains a little known blight on the history of both countries.

***

In 2010, British Prime Minister Gordon Brown apologized for Britain’s part in the forced emigration of children to the colonies: South Africa, Rhodesia, Australia, New Zealand and Canada. In 2014, Britain launched The Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse in England and Wales to investigate claims of sexual assaults-at home and abroad-in schools, churches, children’s homes and the National Health Service, occurring in the years from 1920 to 1970. The purpose of this investigation was to determine how the government failed to protect such children from predators. At the first public hearing specifically concerning the British Child Migration, Gordon Brown testified on 20 July, 2017 that the mass transportation of children to the colonies amounted to “government-enforced trafficking”. He went on to say, “This seems to me as probably the biggest national sex-abuse scandal. Bigger than what people have alleged about individual homes. Bigger in scale, bigger in geographical spread and bigger in the length of time that it went on undetected. I’m shocked by the information that I have seen. We now know that the apology was only half the story.”

Bowing to pressure from organized social media groups, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau tabled a motion apologizing to the remaining British Home Children and their families, on 16 February, 2017. On 7 February, 2018 the House recognized September 28 as annual “British Home Child Day” in Canada.

***